A March Tradition

March 2021

Shared by Sandy Bivens, BIRD Program

sandy.bivens@nashville.gov

Photos by Ed Schneider, Graham Gerdeman, Elizabeth Cook & Nature Center Archives

Mid-March is here. While some are excited about March Madness, I am excitedly watching, listening, and waiting for the arrival of a special bird – the Louisiana Waterthrush. They have been gone since August and should return any minute. I want to see and hear the first one, a March tradition for me (and maybe a friendly competition too).

The Louisiana Waterthrush (aka Parkesia motacilla or LOWA) is an early migrant and heralds the arrival of many more birds heading north to their breeding grounds. Like the blooming spring beauties, it is one of the first signs of spring. This bird is not a thrush but gets the name from its thrush-like plumage and melodious song. The LOWA is a warbler: a songbird in the Wood-Warbler Family (Parulidae) of small to medium sized insectivorous birds with slender, pointed beaks.

Photo shared by Graham Gerdeman

Look for these characteristics of a LOWA: broad white eye-stripe, longish pointed beak, brown plumage, bold streaking, buffy sides, mostly white throat, and long legs. But you may identify it first by its song, behavior, and habitat.

Photo shared by Ed Schneider

The Louisiana Waterthrush is most famous for its loud, ringing, beautiful song. I always hear one before I see it. Sometimes I do not see it all (they are well camouflaged), but I can identify it by the song. I think it sounds like “tree tree tree-ta-whit” and some say “seeup seeup seeup …” but all say it is lovely. As you listen to them more, you can even learn to identify them by their sharp, metallic chip call. And I will admit, I do try to get to the park early this time year, so I might be the first one to hear it – the song so loud I hear it in my car with the windows up in the parking lot as I arrive!

Another way to identify a LOWA is by its behavior – it is known for “wagging” its tail. The species name means “tail-wagger”. It looks like it bobs its tail, but it moves the back half of its body and tail back and forth regularly - while walking and hopping along a creek and perching on rocks and sticks. Look for this “teetering” behavior when you see one!

Photo shared by Elizabeth Cook

To find a LOWA you will have to search in the right habitat. They like forested creeks and moving water. They are streamside birds. They search for food, build their nests, raise their young all along the stream. Protecting forested stream habitats is critical to the survival of Louisiana Waterthrush and many other species.

LOWA eat insects. I counted over 10 insects in this bird’s bill! How many can you count? Can you identify any of them? Maybe it just arrived and has flown all night (they are nocturnal migrants) and was hungry? Or maybe it is feeding 5 hungry nestlings? They eat a wide variety of insects, adults and larvae or nymphs, found in streams – mayflies, caddisflies, midges, craneflies, dragonflies, and beetles to name a few. But they might also eat worms, spiders, crayfish, scorpions, minnows, and even a salamander or frog.

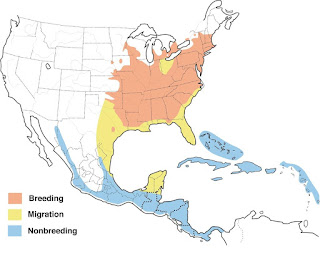

To find a LOWA you will have to search at the right time of year and in the right hemisphere! They migrate to our area in March and find a small stream to nest and start the cycle of their life and then the whole family heads south to Central or South America in August.

Photo shared by Graham Gerdeman

During spring and fall migration another species of Waterthrush passes through our area. The Northern Waterthrush (Parkesia noveboracensis or NOWA), like the LOWA, is a nocturnal migrant and may arrive at Warner Park one morning and immediately start searching for insects in the creek. It might stay several days, singing and eating, and storing fat to fuel the journey further north. You can identify the remarkably similar NOWA by the buffy eye stripe, more yellowish and heavily streaked plumage, streaked throat, and darker undertail coverts. The NOWA also wags its tail but it prefers ponds, swamps, bogs, wetlands, and non-moving water habitats. They are common during migration in our area.

From Birds of the World

The Northern Waterthrush, like the LOWA, is a neotropical migrant, spending the breeding season in North America and the non-breeding season in the tropics.

The Nature Center staff and volunteers regularly monitor the Little Harpeth River for water quality – seining to look for benthic macroinvertebrate organisms (stoneflies, mayflies, etc.) that are sensitive to water pollution. These are the same organisms that are important in the diet of LOWA. The presence of Louisiana Waterthrush in a stream can be an important indicator of water quality.

The Warner Park Banding Station operates a banding station, and BIRD (Bird Information, Research and Data) is a year-round program for bird conservation, habitat protection and education made possible by dedicated staff, volunteers and many partners including Metro Parks, the Warner Park Nature Center and Friends of Warner Parks. With our federal and state permits we regularly catch, band and release birds after we identify, weigh, measure, age, sex, and record this information. We are always thrilled to catch a waterthrush - LOWA and NOWA. And we are always hopeful to recapture them when they return from their southern journey. We have several records of catching the same Louisiana Waterthrush coming back to the same creek to nest the next year. And it takes our breath away each time.

Over 40 years ago I met Dr. Katherine Goodpasture and she quickly became my mentor and friend. “Mrs. G”, as we called her, helped me obtain my bird banding permit and helped us start the Warner Park Banding Station. She had a special relationship with Louisiana Waterthrush, and she shared it with me and others. Early every March she went to her Williamson County farm to try and hear the first LOWA song. It was her tradition. I started trying to hear the first one at Warner Park – a friendly competition with her that I never won, but had great fun trying. This became a tradition with the Warner Park staff and others across the state. Of course, I like to “win” and hear the first one. But mostly I just like to communicate with other LOWA lovers (you know who you are) and learn when the first arrives. Do you have a spring tradition? We hope you come to Warner Park and make one or add another! And enjoy spring!

For More Information about LOWAs:

• The Cornell Lab of Ornithology

No comments:

Post a Comment